The airline travel debacle that unfolded through late December affected millions of travelers, and recovering from it will materially impact at least one airline’s financial health. The unexpected but anticipatable weather events that impacted flight schedules triggered staffing challenges and ultimately caused thousands of cancellations. This was a classic example of an exaggerated ripple effect plaguing planners and project managers across all industries. It prompted me to think through how I have overcome the uncertainties represented in a foreseeable and adverse “Big Event” in the projects I have led. As we have now witnessed the significant downside when such events are not sufficiently considered, I will offer a path to plan for and mitigate the impact of downside risks that we all face.

In a previous blog post, I discussed the dangerous impact of discarding variation in task estimates and dependencies between other tasks or projects. The vast majority of Project Management tools use averages, thus ignoring variation for tasks and the dependencies between tasks, resources, and events. This ensures that a project or a collection of projects will be late. Combined with other factors, such as how we create priorities at the beginning of a project, the issue is not whether the project will miss a deadline but how many times we will have to adjust the deadlines. Your schedules will not be able to adapt to inevitable change, delays will stack up, and your project will be vulnerable to significant hindrances or even complete meltdowns.

The solution to this problem is using LiquidPlanner, which handles both variation (through ranged estimation) and dependencies and flags projects that will be delivered late when preceding tasks are not completed on time.

Introducing the Big Event

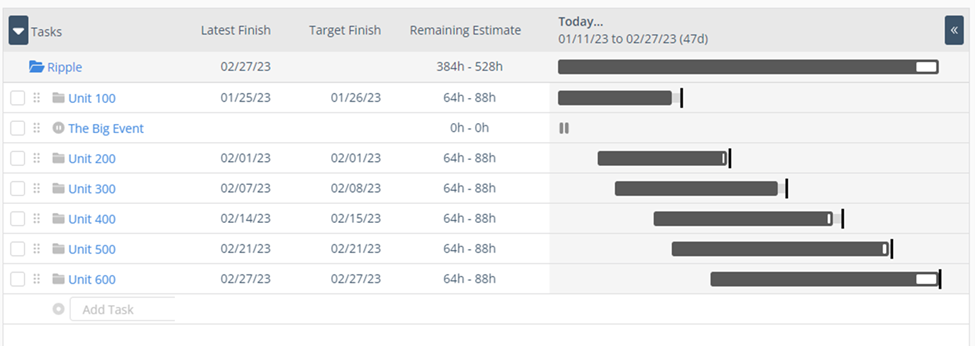

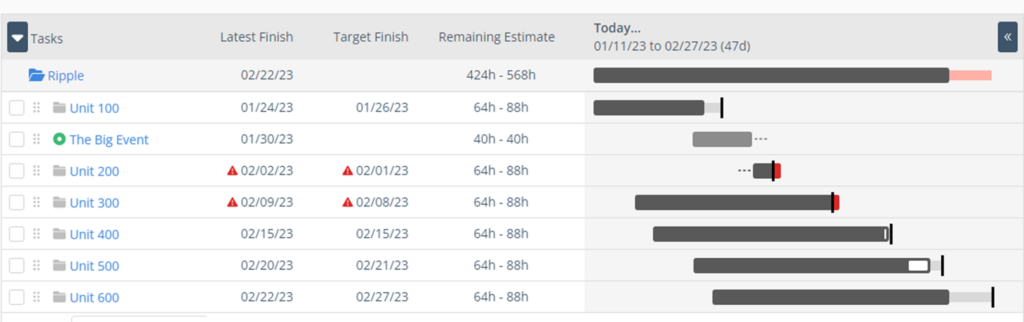

In that blog, we took a simple set of projects and used the Latest Completion Date as their deadlines. We are using the new version of LiquidPlanner below, so we are setting deadlines based on Target Finish based on the Latest Finish, as shown in Figure 1.

“Special cause” variation usually results from some abnormal or unexpected event, such as a significant machine breakdown, weather event, a worker strike, a substantial order, etc. Sometimes it can be predicted, and we can plan our response before, during, and after the event. We know the plan will not be correct, but we have a “What If” tool to keep up with the changing conditions to make intelligent decisions. Accuracy and decision-making will improve as we move closer to the event. Most customers would instead be told the truth about the consequences of a “Big Event” after the fact and then kept in the dark or given entirely unrealistic promises.

This ripple effect is impossible to counter unless we take some action and plan for its occurrence beforehand. Since we are still determining when the event will occur and its duration, some organizations may use the “wait and see” approach. Expensive overtime and frustrated customers are often the results of this type of planning. Let’s look at the variation and dependency model and how we might look ahead and do “What Ifs.”

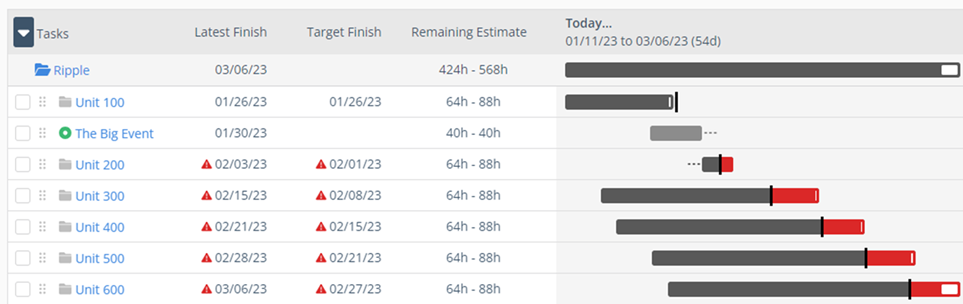

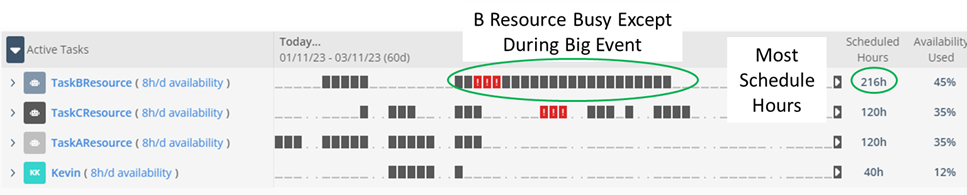

Figure 2 shows the estimated impact of the Big Event without taking any countermeasures. It’s only one scenario based on current predictions. That does not provide an excuse not to do some essential emergency planning.

Recovering from the Big Event

The Classic Version of LiquidPlanner allows you to leverage the power of Critical Chain Project Management, a method yet to be included in the new version of LiquidPlanner. It would show where the problem will appear ahead of time and allow us to draw conclusions on what countermeasures to take. In this case, however, we can use the new version to help us determine what to do. The reason is that the Units all have the same tasks and durations, meaning the busiest resource is the one that is causing the most delay and the one we must improve.

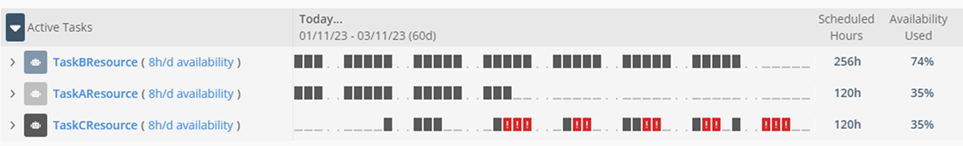

Resource B is clearly the busiest resource from the start of this start frame to the end, being scheduled for 254 hours and using 74% of its Availability. If we can get more out of this resource, we should recover quickly after the Big Event. It is time to run some “What If’s” to see if we add overtime on the weekends and during the week. We can also train A and C resources to do this work. The What Ifs are based on your particular situation.

In our experiments, it becomes clear that no matter how many “What Ifs” we run, it’s clear that we cannot deliver on time for the Customers who have purchased Units 200, Unit 500, and Unit 600 look good if we continue the over time, but it seems like we can stop the extra hours for Resource B before then. Unit 400 will require our attention as the situation changes to ensure it arrives on time. You get the idea. We have a better chance of minimizing the damage if you are proactive instead of reactive. Figure 5 shows the results of one of the experiments.

Conclusion

We can’t prevent Big Events, nor control the type of events they are. It should be clear now that organizations need to have a plan for reacting to a Big Event and dealing with the constant variation. The need for these methods become more evident as Big Events become more predominant – weather, airline, supply chain, and manufacturing issues. Planning the reactions to these events improves communication and projects a sense of calm during a time of chaos. This brings the confidence needed to deal with turmoil and the understanding to deal with management requests for updates when certainty cannot be provided.

Call it self-defense for those dealing with Big Events, Big Management, and Big Voices!

About the Author

Kevin Kohls is the leading authority in using the Theory of Constraints in the Auto Industry. He used LiquidPlanner successfully for engineering to order at Rex Materials to increase OTP by more than 95%. Kevin is also the author of Addicted to Hopium a book about the process of throughput and breaking the habit of guesswork. He can be contacted at kevin.kohls@yahoo.com. View Kevin’s LinkedIn here.

Kevin Kohls is the leading authority in using the Theory of Constraints in the Auto Industry. He used LiquidPlanner successfully for engineering to order at Rex Materials to increase OTP by more than 95%. Kevin is also the author of Addicted to Hopium a book about the process of throughput and breaking the habit of guesswork. He can be contacted at kevin.kohls@yahoo.com. View Kevin’s LinkedIn here.